Link to the leadership product - Collegial Coaching Website

http://collegialcoaching.weebly.com/

Leadership Project Reflection

Cassie Pergament and Geoff Roehm

Introduction

One time, a student in my class tried to throw his desk out the window. Throw might be an exaggeration. It was more like he wanted to put his desk outside the window, on a small ledge that overlooked the street. The student was in 6th grade, and he made this decision in the middle of class, in the middle of my sentence. He calmly stood up, and began dragging his desk toward the window. “Adam, what are you doing?” I asked sincerely. Adam did not respond, instead turning to a classmate and demanding, “Help me put this out there [motioning to the window],” followed by, “You should come too.” I moved between Adam and the window, bewildered by his intent. Adam was small for his age, but he had always been fiery, in both positive and negative ways depending on his mood and his reaction to the material we were covering. He continued to ignore my pleas for an explanation while trying to recruit the bigger students to help him move the desk to his own private veranda. Finally, he looked at me with eyes wide in great frustration and said, “I can’t take this anymore! It’s too boring! I’M GOING OUT THE WINDOW!” I stood and stared, quite befuddled, but quickly realized his classmates were in absolute agreement with Adam’s complaint, and it appeared for a moment that a great desk revolution was about to take place on a twenty-square-foot ledge five stories above a street in central Harlem. I managed to get Adam back in his seat, which diffused the situation, but only after promising I would NEVER be so boring again.

It was my first semester teaching when Adam tried to jump out of my window, and it was the best thing that could have happened. I came to realize that I was so dull, that thirty bright sixth graders would rather risk their lives sitting on the roof than sit in my class. We were reading a book at the time by Walter Dean Meyers, and the story was one that was truly engaging. But I was teaching the book so poorly that it stripped the class of all its life. Worse yet, I had no idea how to teach in the first place. Eventually I found my way. I watched others teach, I found my own professional development, and most importantly I got to know the kids. I can say with confidence that by the end of my first year I was a different teacher, which is only meant to say that I believe students preferred sitting in the room to jumping out of the window. This memory highlights what is most important about being a teacher, which of course is teaching. Pedagogy is not just a word to toss around in graduate programs. It is what teachers do. Teacher preparation programs in the U.S. are woeful in their current ability to meaningfully prepare teachers to be successful in their classrooms. Once in the classroom, most teachers must figure out on their own what works and what doesn’t. And when given opportunities to grow with professional development, teachers often find it unfulfilling or impractical.

Of course there are myriad reasons why students are not always engaged or why students do not always perform as expected, and some of these are out of our control. What we can control is what happens when they are in our presence every day. What we teach is often a topic of great excitement and contention. Arguments over standards and choices regarding curriculum are every day discussions in almost any school in the country. Yet, how we teach is often given much less attention. But it is the how that we can control the most and it is the how that has the biggest single effect on student achievement. Whether a teacher spends more time focusing on the War of 1812 or the Russian Revolution is probably of little consequence in the long run. It is how the teacher engages students, challenges them to think, promotes collaboration and makes topics relevant that will have a much greater impact on students.

This is one of the greatest tricks of a new school leader: creating a culture within a school where teachers feel driven to support one another in improving the craft of teaching in their own and in their colleagues’ rooms. What would such a culture look like? How does a school leader help to foster this culture? What, exactly, are the structures and supports that a school leader can provide to encourage staff to adopt such a culture? Cassie and I came to High Tech High on the verge of our first school leadership positions, and it was our hope that before leaving HTH and embarking on our new careers, we would have a better idea how to answer these questions. We hoped to become leaders who would support our teachers in having the types of conversations about how to teach and how to develop engaging curriculum—so that our teachers would learn more quickly and less painfully what I had learned several years earlier. We would support our teachers to create engaging learning environments, collaborate and learn from one another so that students in our buildings would not feel bored but inspired.

High Tech High is one of the most progressive project-based learning schools in the country. The design principles of Adult World Connection, Personalization, Common Intellectual Mission and Teacher as Designer are true compasses for the staff at HTH. For two new school leaders, this was incredibly fertile ground from which to grow our own understandings about project-based learning and about the structures that support a successful PBL school. What is perhaps most powerful about HTH is the strong culture that permeates all that students and staff do. Teachers create projects that promote inquiry, which leads to a culture of reflection and respect. Structures are in place at each school to allow teachers to collaborate regularly and take on leadership roles. Those who spend time at HTH are not surprised about how it has achieved great success.

That said, there are always areas in which any organization can improve. Independently, Cassie and I each were surprised that the structure of collegial coaching was not being utilized fully. Of the nine schools in the network, there seemed to be wide variance in the commitment toward utilizing the process from both teachers and administrators. The skills demonstrated by teachers in successful project-based learning classrooms are honed over years of experience and learning. It seemed to us that teachers and leaders at HTH could be given greater support in better implementing this important structure. As a potential driver to impact instruction and delivery, collegial coaching was not being utilized to the most powerful extent possible.

Our essential question was: How can we develop structures and a common language to support and increase the efficacy of collegial coaching? Collegial coaching is a process that when done well, meets three essential criteria for successful action taken in schools: it is teacher-driven; it is immediately applicable in the classroom; and it is directly measured by student success. We wanted to ensure that all collegial coaching at HTH was meeting these three criteria.

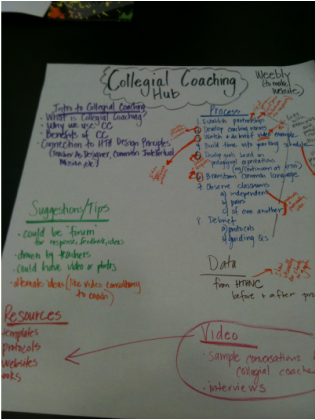

Working with a small group of teachers at two different HTH campuses, we attempted to define what good teaching practices looked like, sounded like and felt like in the classrooms of these teachers. The teachers pushed us to establish a supportive process, but not to make the process so prescriptive that it felt inauthentic. With their help, we collected data on feelings and perceptions of the collegial coaching process at two HTH schools; developed tools to help teachers brainstorm about their own practice and identify areas of strength and areas of need; developed a three step observation cycle that included individual observations, co-observations and peer observations; and developed protocols that assisted in the debrief of observations in a way that was meaningful and not overly prescriptive. We shot video of each one of these steps and hope schools Directors from HTH schools and leaders from around the country will be able to use this video in the future to support collegial coaching at their schools. We collected all of our findings, videos, documents and protocols on a website, aptly named “the Collegial Coaching Hub.”

It was our hope that these structures along with a common language around collegial coaching would help to establish a “culture of critique” around the collegial coaching process. Such a culture results in participants engaging in informal critique on a daily basis. Improvement of the craft becomes a part of the every day conversations of a school and a central part of the purpose of teaching. Establishing cultural norms is not a process that occurs overnight. People must see and feel results before something becomes part of them. I wish that in my first year teaching, I had a collegial coach—a fellow colleague—who could have helped me to deliver more engaging lessons from day one. It took a student named Adam to open my eyes to how much I needed to change and grow. It is our greatest hope that when we lead schools, our teachers will have the support of each other to offer and receive critical feedback so that they can make progress and gains more quickly and in an ongoing and consistent manner.

Understanding: Context

Our primary work with collegial coaching is occurring at two school sites, High Tech High North County (HTHNC) and High Tech Middle Media Arts (HTMMA). Both HTHNC and HTMMA are a part of the eleven-school network that High Tech High operates in San Diego County. All of the HTH schools serve a diverse, lottery-selected student population; and all of the schools embody the High Tech High design principles of personalization, adult world connection, common intellectual mission, and teacher as designer. High Tech High began in 2000 as a single charter high school launched by a coalition of San Diego business leaders and educators. It has grown into a cohesive yet independent network of schools serving grades K-12, a teacher certification program and an innovative Graduate School of Education. It is within the parameters of the Graduate School that our work to improve Collegial Coaching began.

The design principles permeate every aspect of life at High Tech High: the small size of the school, the openness of the facilities, the personalization through advisory, the emphasis on integrated, project-based learning and student exhibitions, the requirement that all students complete internships in the community, and the provision of ample planning time for teacher teams during the work day (from the HTH website). The design principles are extremely relevant in our work as we are focused on developing and researching ideas that fit within the strong existing framework and culture at HTH.

Our focus on two specific schools—HTHNC and HTMMA—helped give us perspective on how to improve collegial coaching at the middle and high school levels. While both schools have a lot in common, they also have different backgrounds and history.

HTHNC opened in 2007 and has grown over the last few years to full capacity and serves students in grades 9-12 from all over San Diego County. The teachers at HTNC foster a project-based learning environment that prides itself in having a common intellectual mission, building meaningful relationships with their community, and celebrating every individual student. The school is both college preparatory and project-based and aims to inspire students to become civic leaders through real-world, authentic learning experiences (from the HTHNC website).

HTMMA opened in 2005 and is a middle school serving 330 students in grades six through eight from all over San Diego County. The teachers at HTMMA pride themselves on enriching young learners with creative pursuits in a challenging, technologically-rich, project-based learning environment. At both schools, teachers are the designers of the project-based curriculum. They focus on developing lessons and projects that highlight adult world connections in the surrounding community and personalization.

Across the HTH organization, approximately 30% of students are Latino, 41.5% are White, 12.5% are Black and 13.7% are Asian. This level of diversity is not only intentional at HTMMA, but is a core part of the design of all High Tech High schools.

We worked closely with subset of teachers to design our project. They met with us several times over the year and offered ideas from their experience and perspective to help make the collegial coaching process more effective. We learned from teachers at both HTMMA and HTHNC about what makes a strong partnership, how a collegial coach can be most supportive while also having a critical lens, and what was missing from collegial coaching at their schools. With their insight, we developed ideas that fueled our work and advanced out thinking.

Project Design Connections

Our work with collegial coaching grew out of a perceived need for greater focus on the continued development and dissemination of best practices in the classroom. The culture at HTH schools lends itself to critique of teaching practices on many levels. Teachers plan, work and even share classrooms and offices with members of a teaching team. Theses teachers share prep periods and often plan extended projects together. There is time built into the schedule each day for the whole staff to meet and teacher study groups are formed in response to school-wide needs. Teachers would often meet to critique one another’s curriculum plans (projects), and would do so by following a standard tuning protocol that would often lead to very rich discussion around the project. And yet, for all of these “teacher-driven” practices, critique around actual teaching practices and instructional delivery varied widely in both quality and frequency. Some teachers would meet often in an informal manner to discuss problems that arose in class. Other teachers would occasionally visit a colleague’s classroom (usually by invitation only). Collegial Coaching was a structure that existed, but was not being utilized with great efficacy, more often manifesting itself as a hurried observation once or twice a year that was thought of as “just one more thing to do.” Collegial coaches were supportive of one another but didn’t always lend a critical eye when talking about instructional delivery and teaching practice. The lack of a common language between partnerships hindered their ability to discuss the specifics around what makes effective instruction.

Despite all of the many positives of the existing collaboration at HTH schools, it is the actual practice of teaching that is the cornerstone of what all educators do. It is the craft that they practice, day after day, year after year. The literature on collegial coaching is clear about its effectiveness. Studies found over and over again that “members of peer-coaching groups exhibited greater long-term retention of new strategies and more appropriate use of new teaching models over time” (Baker and Showers 1984). It was on this type of instructional growth that we wanted to focus. We wanted to see if teachers had a set, consistent schedule, set protocols, and a common language if it would impact teaching practices and instructional delivery over time. In other schools that use coaches in a more hierarchical sense, the coaches often receive training and use a rubric to help them with the language of instruction. We wanted to see if our teachers developed this rich and important language together, it would improve their ability to know what to look for, listen for and notice in one another’s rooms. We felt like improving collegial coaching was quite urgent. With a slim administration in all HTH schools and with a strong belief in facilitated leadership and teachers in the driver seats, if teachers were to help one another grow their craft, they would need more tools and more structure.

Project Design

Pre-Work

The project was implemented over three months with the entire staff at HTHNC and with a teacher focus group at HTMMA. The first step was to meet with a focus group of teachers that we felt represented the diversity of opinions amongst teachers at the school. That meant including diversity of gender and race, experience in the classroom and willingness to participate in the Collegial Coaching model in the past. MacDonald, et al believes “that a product worth producing begins with thoughtful process. Teaching is first of all a process. Leadership is, too... There is no way to solve a complex problem without listening to the perspectives on the problem of all those immersed in it” (2003). Gathering feedback from teacher focus groups proved to be invaluable prior to implementation.

Introduction – Focus Groups

Feedback was not hard to elicit from the participants in the focus group. And although there was not always agreement amongst the group regarding particular ideas around implementation, there were some rather consistent themes that arose regarding the practice of collegial coaching in general. We made our essential question clear to the group up front: how can we develop structures and a common language to support and increase the efficacy of collegial coaching. The most consistent theme we heard was about structuring more time. If there were simply more time dedicated to allowing teachers to observe and reflect, it would happen more. Based on this feedback, we were able to secure more dedicated time (replacing other meetings) for collegial coaching. The next most consistent theme was that the process not be “mandated.” Teachers usually dislike being told what to do. This stems from experience in schools where they have been told what to do and were not given the opportunity to provide input. We were determined to spin this feedback into something positive and useful. Just because teachers may not like being mandated to do things, we knew that once they felt the benefits, they would be on board. We also had confidence that they could help us develop a process that would feel empowering and not belittling. If time were to be set aside specifically for this purpose, it would be hard to say that teachers could choose to participate or not. As we continued to brainstorm, several teachers grasped onto the idea of “common language” in our essential question. They suggested that if teachers were able to establish that language for themselves, and did not have to conform to an external rubric, that this would satisfy the fear of too much external control that led to the questions about whether or not it would feel “mandated.” Finally, over the course of several meetings, our focus groups identified feelings of insecurity around the process in which their schools had approached collegial coaching in the past. Teaching is incredibly personal and teachers take great pride in their work, especially at schools like HTMMA and HTHNC. Teachers fear feeling judged by their colleagues and want to live up to high expectations for themselves and for others. In order to progress positively with collegial coaching, this basic fear needed to surface. . Prior to these focus group meetings, we had grappled with this question of vulnerability and how it might be appeased. We had thought of several strategies to do so, but it was a teacher who came up with the best idea. He suggested partnerships have several rounds of observations of others before observing their partners. That way each teacher can observe on their own simply to learn, and talk about these observations with their partner. , If this step preceded observing and giving feedback to one another, there would already be a precedent for how to interact and it would enable teachers to better overcome the fear of feeling judged. This brilliant and simple suggestion led us to the rounds described below.

Common Language

Before any observations occurred, time was spent for partnerships to build a common language around the collegial coaching process. According to McLaughlin & Talbert (2006) “Shared language reflect[s] the strength of the schools' technical culture around inquiry.” Developing this “technical culture” was vital to ensure that teachers understood how to communicate effectively and in ways that felt meaningful to them. Teachers defined for themselves, with the help of their collegial coach as a sounding board, what a particular practice looked like, sounded like and felt like when being done in an exemplary manner. Teachers used the HTH Continua of Teaching Practices (included in the appendix) as a guiding document. For example, if a partnership sought to improve the ability of “students as self-managers”, the teachers discussed what it would look like, sound like and feel like to be in a classroom with students as strong self-managers. These descriptions would ultimately become a guide (or a self-created rubric) for what to notice in one another’s rooms. Teachers were given dedicated time during morning meetings to brainstorm those practices that they wished to look at more closely and define what they believed that practice looked like when being performed in an exemplary manner. Once teachers defined what practice they wished to work on, the observation cycle began.

Observations

The process consisted of three rounds of observation. The three rounds were meant to be progressive in nature, allowing Collegial Coaching partners to build trust and skill in having conversations around practice. We hoped the process would result in “shared language and understandings [that would] create the basis for school-wide conversations about how [practice] would inform decisions and plans for the future" (McLaughlin & Talbert, 2006). The observations consisted of the following three rounds:

Observation Cycle

1) Individual Observation – This observation consisted of a teacher observing one or several teachers with the only objective being to improve their own practice (not the teacher being observed). The observing teacher looked for instances of a particular practice that they brainstormed and defined with their collegial coach. They had the opportunity to observe any teacher they wished, as all HTH schools operate with an open door policy and teachers are incredibly welcoming to peers who want to spend time in their rooms. Since the goal was to support the observer, the teacher being observed did not participate in a debrief of the observation. Once the observation was complete, the observing teacher debriefed the observation with his or her collegial coach. The collegial coach guided a conversation using a protocol that allowed the observing teacher to discuss and better understand what he or she saw, how it coincided with the practice he or she imagined, and how it could help improve his or her practice.

2) Co-Observation – For the second step of the cycle, the Collegial Coaching partners observed one or more teachers together, each looking for the criteria that he or she previously brainstormed. Once again, they looked to improve their own practice, not that of the teacher being observed. They also hoped to develop effective schools around talking about instruction, using the common language and gained comfort with the collegial coaching protocols. After the observation, the collegial coaching partners debriefed using the same protocol and discussing how the observation helped to refine their vision of the particular practice on which they were each working.

3) Collegial Coach Observation – In the final stage of the cycle that can go on repeatedly, each collegial coach observed his or her partner. This time, the observation took place to benefit the person being observed (although a reflective conversation about practice should always be mutually beneficial). The partners had met several times by this point in the process and each knew well the particular teaching practice the other was concentrating on, which was the focus of the observation. Once the observation was complete, the observing teacher led his or her partner in a conversation, following a protocol, that allowed the observed teacher to dive deeper into what he or she was doing and the implementation and/or development of the particular practice the observed teacher had been working on.

Protocol

Each observation in the above cycle was debriefed using a protocol. The use of protocols can be beneficial on many levels when participating in a reflective exercise, and they were essential in developing the above process. According to Blythe and Allen (2004), "The special province of protocols is in creating a space in which participants, by virtue of their experience-- no matter what the experience is-- can make important contributions to the conversation and, consequently, to the group's learning.” MacDonald, et al (2003) believe that “…as the use of protocols continues to spread from conferences and workshops to everyday settings where colleagues meet to plan and work together…it becomes possible for all of us to imagine a new kind of educational setting-- not cellular but collaborative, not isolated but networked, not opaque but transparent and accountable." We found all of this to be true about the use of protocols. Collegial Coaching partners can often have varying levels of experience in the classroom and teach in different disciplines and grade levels. The differing perspectives that arise from these different experiences could result in miscommunication. The use of a protocol allows participants to focus more deeply on the issues while on a shared playing field. Further, it promotes collaboration in ways that are non-threatening and equitable.

Structures

Prior to the start of the observation cycle, we collected survey data from the whole staff at HTHNC. Survey responses were mostly positive regarding how people felt about collegial coaching. Most participants felt supported by their collegial coach and felt their collegial coach could help them improve as a teacher. However, 70% of respondents stated that their collegial coach was not consistently observing in their classroom. The large majority also responded that the best way to improve the process would be to dedicate more time to completing it. For collegial coaching to be effective, teachers must observe other teachers teaching. Without the ability to observe one’s fellow teachers, the collegial coaching process is not based on any real data. In the case of HTHNC, responses to the survey indicated that teachers felt supported emotionally, but it did not indicate that they were modifying teaching practices as a result of the partnership. This is consistent with the fact that teachers said they were not regularly observing one another, which would be a pre-requisite to discuss how one might grow or change their practice.

Teachers also reported feeling that there was simply not enough time dedicated to implementing collegial coaching. Because a teacher’s day is so full, if there is not specific time dedicated to peer observations it will simply not happen. We have grandiose ideas that teachers will observe on their own free time and sometimes they do. But to have collegial coaching as a systemic process to improve instruction, it needs to be scheduled. Collegial Coaching partners may find one another for a discussion when the day is over, but without observable data such a discussion is bound to be limited. It seemed clear based on teacher responses that setting time aside to allow teachers to observe one another was essential to successful implementation. At HTHNC, staff meetings begin every morning at 7:30am. We replaced four of these staff meetings over the course of the observation cycle to allow teachers time to observe one another and debrief. Two of the meetings were given to teachers as compensated time so that they could observe a colleague during a prep period that day. The other two meetings were set aside to allow collegial coaching teams time to debrief the classes that they observed. (Ideally, six meetings would have been set aside, two for each of the steps in the observation cycle. However, because we began the process mid-year, we were unable to replace enough previously planned meetings to do so. However, the four dedicated mornings allowed teachers to meaningfully engage with the collegial coaching process twice as many times in a semester as they had previously in an entire year.)

Methods/Data Analysis

Data was collected primarily through a staff survey, working with teacher focus groups and interviewing Directors and other leaders in the organization. An all staff survey was distributed prior to beginning the collegial coaching process at High Tech High North County. Results were mixed and indicated a lack of coherence in previous collegial coaching implementation. The feelings that teachers harbored toward the process and toward their own collegial coaching partners were overwhelmingly positive. Teachers felt supported by the relationship they maintained with their partners (Chart 1).

One time, a student in my class tried to throw his desk out the window. Throw might be an exaggeration. It was more like he wanted to put his desk outside the window, on a small ledge that overlooked the street. The student was in 6th grade, and he made this decision in the middle of class, in the middle of my sentence. He calmly stood up, and began dragging his desk toward the window. “Adam, what are you doing?” I asked sincerely. Adam did not respond, instead turning to a classmate and demanding, “Help me put this out there [motioning to the window],” followed by, “You should come too.” I moved between Adam and the window, bewildered by his intent. Adam was small for his age, but he had always been fiery, in both positive and negative ways depending on his mood and his reaction to the material we were covering. He continued to ignore my pleas for an explanation while trying to recruit the bigger students to help him move the desk to his own private veranda. Finally, he looked at me with eyes wide in great frustration and said, “I can’t take this anymore! It’s too boring! I’M GOING OUT THE WINDOW!” I stood and stared, quite befuddled, but quickly realized his classmates were in absolute agreement with Adam’s complaint, and it appeared for a moment that a great desk revolution was about to take place on a twenty-square-foot ledge five stories above a street in central Harlem. I managed to get Adam back in his seat, which diffused the situation, but only after promising I would NEVER be so boring again.

It was my first semester teaching when Adam tried to jump out of my window, and it was the best thing that could have happened. I came to realize that I was so dull, that thirty bright sixth graders would rather risk their lives sitting on the roof than sit in my class. We were reading a book at the time by Walter Dean Meyers, and the story was one that was truly engaging. But I was teaching the book so poorly that it stripped the class of all its life. Worse yet, I had no idea how to teach in the first place. Eventually I found my way. I watched others teach, I found my own professional development, and most importantly I got to know the kids. I can say with confidence that by the end of my first year I was a different teacher, which is only meant to say that I believe students preferred sitting in the room to jumping out of the window. This memory highlights what is most important about being a teacher, which of course is teaching. Pedagogy is not just a word to toss around in graduate programs. It is what teachers do. Teacher preparation programs in the U.S. are woeful in their current ability to meaningfully prepare teachers to be successful in their classrooms. Once in the classroom, most teachers must figure out on their own what works and what doesn’t. And when given opportunities to grow with professional development, teachers often find it unfulfilling or impractical.

Of course there are myriad reasons why students are not always engaged or why students do not always perform as expected, and some of these are out of our control. What we can control is what happens when they are in our presence every day. What we teach is often a topic of great excitement and contention. Arguments over standards and choices regarding curriculum are every day discussions in almost any school in the country. Yet, how we teach is often given much less attention. But it is the how that we can control the most and it is the how that has the biggest single effect on student achievement. Whether a teacher spends more time focusing on the War of 1812 or the Russian Revolution is probably of little consequence in the long run. It is how the teacher engages students, challenges them to think, promotes collaboration and makes topics relevant that will have a much greater impact on students.

This is one of the greatest tricks of a new school leader: creating a culture within a school where teachers feel driven to support one another in improving the craft of teaching in their own and in their colleagues’ rooms. What would such a culture look like? How does a school leader help to foster this culture? What, exactly, are the structures and supports that a school leader can provide to encourage staff to adopt such a culture? Cassie and I came to High Tech High on the verge of our first school leadership positions, and it was our hope that before leaving HTH and embarking on our new careers, we would have a better idea how to answer these questions. We hoped to become leaders who would support our teachers in having the types of conversations about how to teach and how to develop engaging curriculum—so that our teachers would learn more quickly and less painfully what I had learned several years earlier. We would support our teachers to create engaging learning environments, collaborate and learn from one another so that students in our buildings would not feel bored but inspired.

High Tech High is one of the most progressive project-based learning schools in the country. The design principles of Adult World Connection, Personalization, Common Intellectual Mission and Teacher as Designer are true compasses for the staff at HTH. For two new school leaders, this was incredibly fertile ground from which to grow our own understandings about project-based learning and about the structures that support a successful PBL school. What is perhaps most powerful about HTH is the strong culture that permeates all that students and staff do. Teachers create projects that promote inquiry, which leads to a culture of reflection and respect. Structures are in place at each school to allow teachers to collaborate regularly and take on leadership roles. Those who spend time at HTH are not surprised about how it has achieved great success.

That said, there are always areas in which any organization can improve. Independently, Cassie and I each were surprised that the structure of collegial coaching was not being utilized fully. Of the nine schools in the network, there seemed to be wide variance in the commitment toward utilizing the process from both teachers and administrators. The skills demonstrated by teachers in successful project-based learning classrooms are honed over years of experience and learning. It seemed to us that teachers and leaders at HTH could be given greater support in better implementing this important structure. As a potential driver to impact instruction and delivery, collegial coaching was not being utilized to the most powerful extent possible.

Our essential question was: How can we develop structures and a common language to support and increase the efficacy of collegial coaching? Collegial coaching is a process that when done well, meets three essential criteria for successful action taken in schools: it is teacher-driven; it is immediately applicable in the classroom; and it is directly measured by student success. We wanted to ensure that all collegial coaching at HTH was meeting these three criteria.

Working with a small group of teachers at two different HTH campuses, we attempted to define what good teaching practices looked like, sounded like and felt like in the classrooms of these teachers. The teachers pushed us to establish a supportive process, but not to make the process so prescriptive that it felt inauthentic. With their help, we collected data on feelings and perceptions of the collegial coaching process at two HTH schools; developed tools to help teachers brainstorm about their own practice and identify areas of strength and areas of need; developed a three step observation cycle that included individual observations, co-observations and peer observations; and developed protocols that assisted in the debrief of observations in a way that was meaningful and not overly prescriptive. We shot video of each one of these steps and hope schools Directors from HTH schools and leaders from around the country will be able to use this video in the future to support collegial coaching at their schools. We collected all of our findings, videos, documents and protocols on a website, aptly named “the Collegial Coaching Hub.”

It was our hope that these structures along with a common language around collegial coaching would help to establish a “culture of critique” around the collegial coaching process. Such a culture results in participants engaging in informal critique on a daily basis. Improvement of the craft becomes a part of the every day conversations of a school and a central part of the purpose of teaching. Establishing cultural norms is not a process that occurs overnight. People must see and feel results before something becomes part of them. I wish that in my first year teaching, I had a collegial coach—a fellow colleague—who could have helped me to deliver more engaging lessons from day one. It took a student named Adam to open my eyes to how much I needed to change and grow. It is our greatest hope that when we lead schools, our teachers will have the support of each other to offer and receive critical feedback so that they can make progress and gains more quickly and in an ongoing and consistent manner.

Understanding: Context

Our primary work with collegial coaching is occurring at two school sites, High Tech High North County (HTHNC) and High Tech Middle Media Arts (HTMMA). Both HTHNC and HTMMA are a part of the eleven-school network that High Tech High operates in San Diego County. All of the HTH schools serve a diverse, lottery-selected student population; and all of the schools embody the High Tech High design principles of personalization, adult world connection, common intellectual mission, and teacher as designer. High Tech High began in 2000 as a single charter high school launched by a coalition of San Diego business leaders and educators. It has grown into a cohesive yet independent network of schools serving grades K-12, a teacher certification program and an innovative Graduate School of Education. It is within the parameters of the Graduate School that our work to improve Collegial Coaching began.

The design principles permeate every aspect of life at High Tech High: the small size of the school, the openness of the facilities, the personalization through advisory, the emphasis on integrated, project-based learning and student exhibitions, the requirement that all students complete internships in the community, and the provision of ample planning time for teacher teams during the work day (from the HTH website). The design principles are extremely relevant in our work as we are focused on developing and researching ideas that fit within the strong existing framework and culture at HTH.

Our focus on two specific schools—HTHNC and HTMMA—helped give us perspective on how to improve collegial coaching at the middle and high school levels. While both schools have a lot in common, they also have different backgrounds and history.

HTHNC opened in 2007 and has grown over the last few years to full capacity and serves students in grades 9-12 from all over San Diego County. The teachers at HTNC foster a project-based learning environment that prides itself in having a common intellectual mission, building meaningful relationships with their community, and celebrating every individual student. The school is both college preparatory and project-based and aims to inspire students to become civic leaders through real-world, authentic learning experiences (from the HTHNC website).

HTMMA opened in 2005 and is a middle school serving 330 students in grades six through eight from all over San Diego County. The teachers at HTMMA pride themselves on enriching young learners with creative pursuits in a challenging, technologically-rich, project-based learning environment. At both schools, teachers are the designers of the project-based curriculum. They focus on developing lessons and projects that highlight adult world connections in the surrounding community and personalization.

Across the HTH organization, approximately 30% of students are Latino, 41.5% are White, 12.5% are Black and 13.7% are Asian. This level of diversity is not only intentional at HTMMA, but is a core part of the design of all High Tech High schools.

We worked closely with subset of teachers to design our project. They met with us several times over the year and offered ideas from their experience and perspective to help make the collegial coaching process more effective. We learned from teachers at both HTMMA and HTHNC about what makes a strong partnership, how a collegial coach can be most supportive while also having a critical lens, and what was missing from collegial coaching at their schools. With their insight, we developed ideas that fueled our work and advanced out thinking.

Project Design Connections

Our work with collegial coaching grew out of a perceived need for greater focus on the continued development and dissemination of best practices in the classroom. The culture at HTH schools lends itself to critique of teaching practices on many levels. Teachers plan, work and even share classrooms and offices with members of a teaching team. Theses teachers share prep periods and often plan extended projects together. There is time built into the schedule each day for the whole staff to meet and teacher study groups are formed in response to school-wide needs. Teachers would often meet to critique one another’s curriculum plans (projects), and would do so by following a standard tuning protocol that would often lead to very rich discussion around the project. And yet, for all of these “teacher-driven” practices, critique around actual teaching practices and instructional delivery varied widely in both quality and frequency. Some teachers would meet often in an informal manner to discuss problems that arose in class. Other teachers would occasionally visit a colleague’s classroom (usually by invitation only). Collegial Coaching was a structure that existed, but was not being utilized with great efficacy, more often manifesting itself as a hurried observation once or twice a year that was thought of as “just one more thing to do.” Collegial coaches were supportive of one another but didn’t always lend a critical eye when talking about instructional delivery and teaching practice. The lack of a common language between partnerships hindered their ability to discuss the specifics around what makes effective instruction.

Despite all of the many positives of the existing collaboration at HTH schools, it is the actual practice of teaching that is the cornerstone of what all educators do. It is the craft that they practice, day after day, year after year. The literature on collegial coaching is clear about its effectiveness. Studies found over and over again that “members of peer-coaching groups exhibited greater long-term retention of new strategies and more appropriate use of new teaching models over time” (Baker and Showers 1984). It was on this type of instructional growth that we wanted to focus. We wanted to see if teachers had a set, consistent schedule, set protocols, and a common language if it would impact teaching practices and instructional delivery over time. In other schools that use coaches in a more hierarchical sense, the coaches often receive training and use a rubric to help them with the language of instruction. We wanted to see if our teachers developed this rich and important language together, it would improve their ability to know what to look for, listen for and notice in one another’s rooms. We felt like improving collegial coaching was quite urgent. With a slim administration in all HTH schools and with a strong belief in facilitated leadership and teachers in the driver seats, if teachers were to help one another grow their craft, they would need more tools and more structure.

Project Design

Pre-Work

The project was implemented over three months with the entire staff at HTHNC and with a teacher focus group at HTMMA. The first step was to meet with a focus group of teachers that we felt represented the diversity of opinions amongst teachers at the school. That meant including diversity of gender and race, experience in the classroom and willingness to participate in the Collegial Coaching model in the past. MacDonald, et al believes “that a product worth producing begins with thoughtful process. Teaching is first of all a process. Leadership is, too... There is no way to solve a complex problem without listening to the perspectives on the problem of all those immersed in it” (2003). Gathering feedback from teacher focus groups proved to be invaluable prior to implementation.

Introduction – Focus Groups

Feedback was not hard to elicit from the participants in the focus group. And although there was not always agreement amongst the group regarding particular ideas around implementation, there were some rather consistent themes that arose regarding the practice of collegial coaching in general. We made our essential question clear to the group up front: how can we develop structures and a common language to support and increase the efficacy of collegial coaching. The most consistent theme we heard was about structuring more time. If there were simply more time dedicated to allowing teachers to observe and reflect, it would happen more. Based on this feedback, we were able to secure more dedicated time (replacing other meetings) for collegial coaching. The next most consistent theme was that the process not be “mandated.” Teachers usually dislike being told what to do. This stems from experience in schools where they have been told what to do and were not given the opportunity to provide input. We were determined to spin this feedback into something positive and useful. Just because teachers may not like being mandated to do things, we knew that once they felt the benefits, they would be on board. We also had confidence that they could help us develop a process that would feel empowering and not belittling. If time were to be set aside specifically for this purpose, it would be hard to say that teachers could choose to participate or not. As we continued to brainstorm, several teachers grasped onto the idea of “common language” in our essential question. They suggested that if teachers were able to establish that language for themselves, and did not have to conform to an external rubric, that this would satisfy the fear of too much external control that led to the questions about whether or not it would feel “mandated.” Finally, over the course of several meetings, our focus groups identified feelings of insecurity around the process in which their schools had approached collegial coaching in the past. Teaching is incredibly personal and teachers take great pride in their work, especially at schools like HTMMA and HTHNC. Teachers fear feeling judged by their colleagues and want to live up to high expectations for themselves and for others. In order to progress positively with collegial coaching, this basic fear needed to surface. . Prior to these focus group meetings, we had grappled with this question of vulnerability and how it might be appeased. We had thought of several strategies to do so, but it was a teacher who came up with the best idea. He suggested partnerships have several rounds of observations of others before observing their partners. That way each teacher can observe on their own simply to learn, and talk about these observations with their partner. , If this step preceded observing and giving feedback to one another, there would already be a precedent for how to interact and it would enable teachers to better overcome the fear of feeling judged. This brilliant and simple suggestion led us to the rounds described below.

Common Language

Before any observations occurred, time was spent for partnerships to build a common language around the collegial coaching process. According to McLaughlin & Talbert (2006) “Shared language reflect[s] the strength of the schools' technical culture around inquiry.” Developing this “technical culture” was vital to ensure that teachers understood how to communicate effectively and in ways that felt meaningful to them. Teachers defined for themselves, with the help of their collegial coach as a sounding board, what a particular practice looked like, sounded like and felt like when being done in an exemplary manner. Teachers used the HTH Continua of Teaching Practices (included in the appendix) as a guiding document. For example, if a partnership sought to improve the ability of “students as self-managers”, the teachers discussed what it would look like, sound like and feel like to be in a classroom with students as strong self-managers. These descriptions would ultimately become a guide (or a self-created rubric) for what to notice in one another’s rooms. Teachers were given dedicated time during morning meetings to brainstorm those practices that they wished to look at more closely and define what they believed that practice looked like when being performed in an exemplary manner. Once teachers defined what practice they wished to work on, the observation cycle began.

Observations

The process consisted of three rounds of observation. The three rounds were meant to be progressive in nature, allowing Collegial Coaching partners to build trust and skill in having conversations around practice. We hoped the process would result in “shared language and understandings [that would] create the basis for school-wide conversations about how [practice] would inform decisions and plans for the future" (McLaughlin & Talbert, 2006). The observations consisted of the following three rounds:

Observation Cycle

1) Individual Observation – This observation consisted of a teacher observing one or several teachers with the only objective being to improve their own practice (not the teacher being observed). The observing teacher looked for instances of a particular practice that they brainstormed and defined with their collegial coach. They had the opportunity to observe any teacher they wished, as all HTH schools operate with an open door policy and teachers are incredibly welcoming to peers who want to spend time in their rooms. Since the goal was to support the observer, the teacher being observed did not participate in a debrief of the observation. Once the observation was complete, the observing teacher debriefed the observation with his or her collegial coach. The collegial coach guided a conversation using a protocol that allowed the observing teacher to discuss and better understand what he or she saw, how it coincided with the practice he or she imagined, and how it could help improve his or her practice.

2) Co-Observation – For the second step of the cycle, the Collegial Coaching partners observed one or more teachers together, each looking for the criteria that he or she previously brainstormed. Once again, they looked to improve their own practice, not that of the teacher being observed. They also hoped to develop effective schools around talking about instruction, using the common language and gained comfort with the collegial coaching protocols. After the observation, the collegial coaching partners debriefed using the same protocol and discussing how the observation helped to refine their vision of the particular practice on which they were each working.

3) Collegial Coach Observation – In the final stage of the cycle that can go on repeatedly, each collegial coach observed his or her partner. This time, the observation took place to benefit the person being observed (although a reflective conversation about practice should always be mutually beneficial). The partners had met several times by this point in the process and each knew well the particular teaching practice the other was concentrating on, which was the focus of the observation. Once the observation was complete, the observing teacher led his or her partner in a conversation, following a protocol, that allowed the observed teacher to dive deeper into what he or she was doing and the implementation and/or development of the particular practice the observed teacher had been working on.

Protocol

Each observation in the above cycle was debriefed using a protocol. The use of protocols can be beneficial on many levels when participating in a reflective exercise, and they were essential in developing the above process. According to Blythe and Allen (2004), "The special province of protocols is in creating a space in which participants, by virtue of their experience-- no matter what the experience is-- can make important contributions to the conversation and, consequently, to the group's learning.” MacDonald, et al (2003) believe that “…as the use of protocols continues to spread from conferences and workshops to everyday settings where colleagues meet to plan and work together…it becomes possible for all of us to imagine a new kind of educational setting-- not cellular but collaborative, not isolated but networked, not opaque but transparent and accountable." We found all of this to be true about the use of protocols. Collegial Coaching partners can often have varying levels of experience in the classroom and teach in different disciplines and grade levels. The differing perspectives that arise from these different experiences could result in miscommunication. The use of a protocol allows participants to focus more deeply on the issues while on a shared playing field. Further, it promotes collaboration in ways that are non-threatening and equitable.

Structures

Prior to the start of the observation cycle, we collected survey data from the whole staff at HTHNC. Survey responses were mostly positive regarding how people felt about collegial coaching. Most participants felt supported by their collegial coach and felt their collegial coach could help them improve as a teacher. However, 70% of respondents stated that their collegial coach was not consistently observing in their classroom. The large majority also responded that the best way to improve the process would be to dedicate more time to completing it. For collegial coaching to be effective, teachers must observe other teachers teaching. Without the ability to observe one’s fellow teachers, the collegial coaching process is not based on any real data. In the case of HTHNC, responses to the survey indicated that teachers felt supported emotionally, but it did not indicate that they were modifying teaching practices as a result of the partnership. This is consistent with the fact that teachers said they were not regularly observing one another, which would be a pre-requisite to discuss how one might grow or change their practice.

Teachers also reported feeling that there was simply not enough time dedicated to implementing collegial coaching. Because a teacher’s day is so full, if there is not specific time dedicated to peer observations it will simply not happen. We have grandiose ideas that teachers will observe on their own free time and sometimes they do. But to have collegial coaching as a systemic process to improve instruction, it needs to be scheduled. Collegial Coaching partners may find one another for a discussion when the day is over, but without observable data such a discussion is bound to be limited. It seemed clear based on teacher responses that setting time aside to allow teachers to observe one another was essential to successful implementation. At HTHNC, staff meetings begin every morning at 7:30am. We replaced four of these staff meetings over the course of the observation cycle to allow teachers time to observe one another and debrief. Two of the meetings were given to teachers as compensated time so that they could observe a colleague during a prep period that day. The other two meetings were set aside to allow collegial coaching teams time to debrief the classes that they observed. (Ideally, six meetings would have been set aside, two for each of the steps in the observation cycle. However, because we began the process mid-year, we were unable to replace enough previously planned meetings to do so. However, the four dedicated mornings allowed teachers to meaningfully engage with the collegial coaching process twice as many times in a semester as they had previously in an entire year.)

Methods/Data Analysis

Data was collected primarily through a staff survey, working with teacher focus groups and interviewing Directors and other leaders in the organization. An all staff survey was distributed prior to beginning the collegial coaching process at High Tech High North County. Results were mixed and indicated a lack of coherence in previous collegial coaching implementation. The feelings that teachers harbored toward the process and toward their own collegial coaching partners were overwhelmingly positive. Teachers felt supported by the relationship they maintained with their partners (Chart 1).

Developing a strong relationship with one’s collegial coaching partner is a significant step in establishing an effective collegial coaching process. This relationship needs to be one that allows for clear communication (a common language) and the ability to accept feedback. Chart 1 indicates that a strong foundation exists upon which to build collegial coaching. The data in Chart 2 is more mixed. It indicates that some teams have begun the process of focusing on specific classroom teaching practices for improvement, which is the goal of the process. But nearly half of the respondents indicated that significant work had not been done to identify specific skills for improvement.

When asked specific questions about the frequency with which teachers were observing one another, yet another picture arose (Chart 3).

Over 70% of respondents to the above question did not believe that their collegial coach was observing consistently. Although teachers enjoyed the relationships they had with their collegial coach, a preponderance of teachers had not begun the process of identifying skills to work on and no deep work could occur without conducting classroom observations. Classroom observations are a cornerstone of an effective collegial coaching process, as they provide the data around which the “coaching” can occur.

Teacher and Director Feedback

We posed questions to teacher and director focus groups at HTHNC and HTMMA to collect further anecdotal data. Teacher responses in focus groups were consistent across both school sites. Not surprisingly, director responses closely mirrored teacher responses. Most consistent of all responses regarded the amount of time dedicated to the collegial coaching process. The scheduled time was an issue for teachers. No matter what the topic, being able to have dedicated time in the day seemed to be the most precious resource and pressing concern that a Director would need to address in order to improve collegial coaching at their site. Directors also stated that there never seemed to be enough time to dedicate to the process to make it truly effective. Many directors felt that it would be their responsibility to ensure that there was more time set aside in the future.

Similarly, both teachers and directors believed that the collegial coaching process helped to foster positive relationships amongst staff. This seemed to suggest that both teachers and school leaders did not view collegial coaching as evaluative, rather as a support system for quality instruction.

One place where teachers and directors diverged significantly was around the use of video. Directors nearly unanimously believed that the use of video should be an essential part of the collegial coaching practice and one that would help to support its efficacy. While there were pockets of teachers that agreed with this position, there were many teachers who did not desire to make video a part of the process, their hesitancy arising out of feelings of insecurity about what they might see and how they might be subsequently evaluated (although there has not been any suggestion from Directors that video or collegial coaching would be used as an evaluative tool).

Discussion

Effectiveness of Work

It is difficult to judge the effectiveness of the work in which we were engaged for several reasons. First, true effectiveness can only be judged by one ultimate measure, which is whether or not collegial coaching is improving student achievement and positively impacting the instructional delivery and culture of critique. The ultimate goal is to prepare all students to be successful and happy citizens, who are engaged in learning and advocates for their own well-being. While benchmarks exist to measure our progress, the collegial coaching process that we began is only in its infancy. We have no student data to tell us how well we are progressing.

Anecdotal teacher responses collected toward the end of the process were positive. The greater time set aside in the schedule to engage in collegial coaching was received well and many teachers remarked that they were looking forward to collegial coaching next year. We presented our work at a meeting for Directors of all High Tech High schools as well as CMO staff and leaders of the HTH Graduate School and again received positive anecdotal data. Directors responded almost unanimously that they planned to use this process next year to introduce and maintain Collegial Coaching at their schools. If they do so, then we would be in a position to collect a significant amount of data over the year and across HTH schools and campuses. However, even with full implementation and more time to gather data, it would be difficult to measure effectiveness. That is not meant to dismiss what we could learn about the process in a year’s time or suggest that it would not be beneficial for kids during that time. In fact, the collegial coaching model, implemented well for a full school year, could have an incredibly positive effect on classroom practices. We realized that this model is one that is only truly effective when it becomes a part of the culture and fabric of a school. Collegial coaching is an important way for schools to encourage reflective practice, refinement and critique. No matter where one teaches, that is work is never over for an educator.

We highly recommend for school leaders to implement and invest in collegial coaching as a way to improve the culture of critique and to have positive impacts on instruction across classrooms. Collegial coaching can accomplish some very practical and important things in one year. If the process is made a focus for the year, it can lay the foundation for school-wide common language and goals for instruction; it can prioritize the act of teaching (something that does not happen in all schools); it can promote transparency; it can foster accountability; and it can encourage the free flow of effective ideas from one classroom to another in practical and implementable ways. The schools where we were lucky enough to do this work—HTHNC and HTMMA—have incredibly strong and positive cultures with faculty who love to engage and collaborate with one another. Despite a strong collaborative environment, there are obstacles to overcome. We are hopeful that the process we have designed and the materials we used and developed will support school leaders in more effective implementation of collegial coaching. Even in a school like ours where all teachers routinely take on leadership roles and share their work, this process required great attention to properly implement. The obstacles to reflective practice, even in strong, positive and transparent cultures, are many and this framework aims to overcome some of them.

At its heart, the process in which we were engaged was about reflection. Collegial Coaching, and any other reflective process, asks people to stop what they are doing and examine it closely. This is difficult work for anyone. Teachers spend their days tending to the busy and complicated lives of hundreds of children and the best teachers are those who know their students well and leverage that knowledge to individualize instruction for each student to learn and grow. This is a hard job. To ask teachers not just to slow down, but to stop what they are doing and simply reflect can seem counterproductive. Where is the time? If reflective processes such as collegial coaching are to be implemented effectively, the culture of the institutions in which they are being implemented must be one that allows, encourages and provides structures for teachers to stop what they are doing and reflect. It must be a culture that believes that slowing down on a regular basis is the best way to speed up. A school leader must believe (and be able to prove) that teacher reflection, an ostensibly passive activity, is the best and most efficient way to reach student achievement goals. For truly reflective practice to work, the culture of a school must be one that supports and celebrates teachers who work hard to improve through reflection. It must be good to identify shortcomings, not something that receives a reprimand. Colleagues must care for and support one another in this process, and school leaders must celebrate it publicly.

The combination of these obstacles is formidable when trying to establish a culture that supports reflective practice. We live in an ultra-fast-paced world that rewards high test scores over meaningful growth. Many societal and educational norms work against establishing such a culture. But the more one engages with such a culture the more one feels and knows it is the right thing to do and will have the most meaningful long term results not only for themselves, but also for their students.

When I think about Adam now, I often picture him sitting outside of the window on that ledge in Harlem, as if he had succeeded in jumping out of the window from my classroom to escape the boredom. Knowing what I know now, I often wonder if a structure like collegial coaching had been in place that allowed me to reflect and see how un-engaging my instruction, would I have changed more quickly and helped Adam to love learning under my wings. In many ways, successful teaching is the ability to figuratively coax students into the room; to invite them to sit with fresh ideas; to work with them to find all of the beauty and potential in the world. I hope in some small way this process is a step toward inviting Adam back into the room and fostering a love of learning that would grow inside of him. .

When asked specific questions about the frequency with which teachers were observing one another, yet another picture arose (Chart 3).

Over 70% of respondents to the above question did not believe that their collegial coach was observing consistently. Although teachers enjoyed the relationships they had with their collegial coach, a preponderance of teachers had not begun the process of identifying skills to work on and no deep work could occur without conducting classroom observations. Classroom observations are a cornerstone of an effective collegial coaching process, as they provide the data around which the “coaching” can occur.

Teacher and Director Feedback

We posed questions to teacher and director focus groups at HTHNC and HTMMA to collect further anecdotal data. Teacher responses in focus groups were consistent across both school sites. Not surprisingly, director responses closely mirrored teacher responses. Most consistent of all responses regarded the amount of time dedicated to the collegial coaching process. The scheduled time was an issue for teachers. No matter what the topic, being able to have dedicated time in the day seemed to be the most precious resource and pressing concern that a Director would need to address in order to improve collegial coaching at their site. Directors also stated that there never seemed to be enough time to dedicate to the process to make it truly effective. Many directors felt that it would be their responsibility to ensure that there was more time set aside in the future.

Similarly, both teachers and directors believed that the collegial coaching process helped to foster positive relationships amongst staff. This seemed to suggest that both teachers and school leaders did not view collegial coaching as evaluative, rather as a support system for quality instruction.

One place where teachers and directors diverged significantly was around the use of video. Directors nearly unanimously believed that the use of video should be an essential part of the collegial coaching practice and one that would help to support its efficacy. While there were pockets of teachers that agreed with this position, there were many teachers who did not desire to make video a part of the process, their hesitancy arising out of feelings of insecurity about what they might see and how they might be subsequently evaluated (although there has not been any suggestion from Directors that video or collegial coaching would be used as an evaluative tool).

Discussion

Effectiveness of Work

It is difficult to judge the effectiveness of the work in which we were engaged for several reasons. First, true effectiveness can only be judged by one ultimate measure, which is whether or not collegial coaching is improving student achievement and positively impacting the instructional delivery and culture of critique. The ultimate goal is to prepare all students to be successful and happy citizens, who are engaged in learning and advocates for their own well-being. While benchmarks exist to measure our progress, the collegial coaching process that we began is only in its infancy. We have no student data to tell us how well we are progressing.

Anecdotal teacher responses collected toward the end of the process were positive. The greater time set aside in the schedule to engage in collegial coaching was received well and many teachers remarked that they were looking forward to collegial coaching next year. We presented our work at a meeting for Directors of all High Tech High schools as well as CMO staff and leaders of the HTH Graduate School and again received positive anecdotal data. Directors responded almost unanimously that they planned to use this process next year to introduce and maintain Collegial Coaching at their schools. If they do so, then we would be in a position to collect a significant amount of data over the year and across HTH schools and campuses. However, even with full implementation and more time to gather data, it would be difficult to measure effectiveness. That is not meant to dismiss what we could learn about the process in a year’s time or suggest that it would not be beneficial for kids during that time. In fact, the collegial coaching model, implemented well for a full school year, could have an incredibly positive effect on classroom practices. We realized that this model is one that is only truly effective when it becomes a part of the culture and fabric of a school. Collegial coaching is an important way for schools to encourage reflective practice, refinement and critique. No matter where one teaches, that is work is never over for an educator.

We highly recommend for school leaders to implement and invest in collegial coaching as a way to improve the culture of critique and to have positive impacts on instruction across classrooms. Collegial coaching can accomplish some very practical and important things in one year. If the process is made a focus for the year, it can lay the foundation for school-wide common language and goals for instruction; it can prioritize the act of teaching (something that does not happen in all schools); it can promote transparency; it can foster accountability; and it can encourage the free flow of effective ideas from one classroom to another in practical and implementable ways. The schools where we were lucky enough to do this work—HTHNC and HTMMA—have incredibly strong and positive cultures with faculty who love to engage and collaborate with one another. Despite a strong collaborative environment, there are obstacles to overcome. We are hopeful that the process we have designed and the materials we used and developed will support school leaders in more effective implementation of collegial coaching. Even in a school like ours where all teachers routinely take on leadership roles and share their work, this process required great attention to properly implement. The obstacles to reflective practice, even in strong, positive and transparent cultures, are many and this framework aims to overcome some of them.

At its heart, the process in which we were engaged was about reflection. Collegial Coaching, and any other reflective process, asks people to stop what they are doing and examine it closely. This is difficult work for anyone. Teachers spend their days tending to the busy and complicated lives of hundreds of children and the best teachers are those who know their students well and leverage that knowledge to individualize instruction for each student to learn and grow. This is a hard job. To ask teachers not just to slow down, but to stop what they are doing and simply reflect can seem counterproductive. Where is the time? If reflective processes such as collegial coaching are to be implemented effectively, the culture of the institutions in which they are being implemented must be one that allows, encourages and provides structures for teachers to stop what they are doing and reflect. It must be a culture that believes that slowing down on a regular basis is the best way to speed up. A school leader must believe (and be able to prove) that teacher reflection, an ostensibly passive activity, is the best and most efficient way to reach student achievement goals. For truly reflective practice to work, the culture of a school must be one that supports and celebrates teachers who work hard to improve through reflection. It must be good to identify shortcomings, not something that receives a reprimand. Colleagues must care for and support one another in this process, and school leaders must celebrate it publicly.

The combination of these obstacles is formidable when trying to establish a culture that supports reflective practice. We live in an ultra-fast-paced world that rewards high test scores over meaningful growth. Many societal and educational norms work against establishing such a culture. But the more one engages with such a culture the more one feels and knows it is the right thing to do and will have the most meaningful long term results not only for themselves, but also for their students.

When I think about Adam now, I often picture him sitting outside of the window on that ledge in Harlem, as if he had succeeded in jumping out of the window from my classroom to escape the boredom. Knowing what I know now, I often wonder if a structure like collegial coaching had been in place that allowed me to reflect and see how un-engaging my instruction, would I have changed more quickly and helped Adam to love learning under my wings. In many ways, successful teaching is the ability to figuratively coax students into the room; to invite them to sit with fresh ideas; to work with them to find all of the beauty and potential in the world. I hope in some small way this process is a step toward inviting Adam back into the room and fostering a love of learning that would grow inside of him. .